Dave Laslett: Photographing the culturally rich lives of Australia’s First Peoples

**Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this story may contain images of deceased persons which may cause sadness or distress.**

An outlier, an aberration, a rebel with a cause, a loner, many a label can be thrown at Dave Laslett, but few would encapsulate his inimitable way of living and his genius. The photographer unencumbered by societal norms abhors fixed addresses, instead roams and parks his military troop carrier – which doubles up as his home on wheels – wherever his heart desires. The distant interiors of South Australia to the undulating APY lands, no place is too remote for Dave. This purposeful separation from the urban landscape not only enables him to live an almost esoteric life but also facilitates the manifestation of his lifelong ambition, chronicling the lives of Australia’s First Peoples. Indigenous stories are often swathed in partisan politics, deep-rooted ideology of colonialism, general racism or overcompensation; rarely narrated or viewed sans various biases. It is a flaw that the 42-year-old, through his work, tries to remedy.

Last few years, Dave has lived off the grid, assiduously bringing to light Indigenous Australians’ struggles, pathos, and hard-fought achievements. His photography is slowly transcending entertainment to create a powerful literature on the lives of Australia’s First Peoples. If there is an aspect more interesting than Dave’s work, it is his unique lifestyle that thrives outside the cloud of urbanism.

In conversation with TAL, the Australian opens up about a teenage incident that changed his life forever, his inspiring mother and eccentric lifestyle.

We know you live an interesting life now, but what about your childhood? Was it an adventurous upbringing?

I was born in 1978 in Port Augusta Hospital, South Australia. Till I was four, we lived opposite the main power plant in a small three-bedroom house. My family moved a lot during my formative years which became a precursor for my transient, non-conforming life unrestrained by regular societal expectations.

My childhood and teenage years were a mixed bag. I remember sitting on the roof of a troop carrier, holding onto jerry cans for dear life as we drove over a sea of red sand hills; my Nan’s suicide; thinking I could outrun dad at the age of five and my subsequent indignant shock. A lot of these experiences led to my obsession with the concept of perception versus reality. To challenge external perceptions and expectations is something I just naturally do. Why is a weed a weed; why the blue I see is different for the next person? I want to fundamentally understand my reality but also how that translates into another person’s experience.

Was photography a childhood passion? And, growing up who inspired you the most?

One of the places we lived, while growing up, was near the Dandenong Hills just outside Melbourne. One day we had a travelling doctor visit our family home. That night my parents couldn’t find me anywhere and started frantically searching for me. After what seemed like an eternity for them, they saw sudden bursts of lights illuminating the trees in the garden. They rushed there and found me sitting cross-legged fiddling with the doctor’s camera lights. I think I was five at the time. That experience was one of many that nudged me into the field of photography.

As a child, my mother was my biggest inspiration. I remember her being a part of the local theatre production in 1985. The producer asked if anyone knew how to make smoke that stayed on the ground, and she volunteered straight away. She didn’t know how to create that effect and wasn’t even aware of the terminology. Still, she volunteered and figured it out by mixing various chemicals available, as her colleagues on stage enthralled the audience.

That incident laid the foundation of my never say never attitude. The confidence that nothing is insurmountable, and everything is possible if given a heartfelt try helped me master many things in life; none of which would have been possible without these early seemingly insignificant life lessons.

I don’t see myself as a professional photographer, although by industry standards, I do solely make my living from the camera. For me, it is a device that facilitates my overall creativity.

My background is in audio engineering, design and festival lighting, which lead me to adopt and use the formula of input, processing and output in all elements. My method is steeped in hyper-focus. I have merged my profession, life and hobbies into a single feature. This style helps me create a resource base which is streamlined and targeted, allowing for a constant balance of research and development, recovery or performance mode.

Everything about you is unique and gives much fodder to a writer. Let’s start with the way you live – in complete isolation, close to the land and in an old military carrier! How and why did you embrace this type of living? And, how did you come across the vehicle you call home?

A tremendous amount of research went into the decision and the consequent selection of the ADF Land Rover 110 series. It wasn’t an easy option, but for my intended purpose, this vehicle was the only choice.

The world is full of distracting elements that consume our lives and draw us away from joy. I went into the desert because I wanted to live with purpose and intent, remove unwanted interruptions that dilute the process and aim for true creativity that comes from clarity not clouded by societal obligations and behaviours.

I am an admirer of resources that is multipurpose, like the military troop carrier. The vehicle, along with enabling constant creativity, also takes me to places others cannot go. It allows for sustainable off-grid 12v / 240v power, reliable water supply, storage and transport of a large number of production equipment. Also, it offers a great rooftop spot to have meals overlooking the ranges.

Given your style of living, would it be wrong to assume that you are a loner, an introvert, and prefer solitude over company?

It takes me four days of isolation to be genuinely present and feel connected to the space I am in. I am free to do everything or nothing. I’m a firm believer in choice; everyone should have that right. I crave for meaningful discussions, and the empath in me is drawn to intense, quality, and addictive conversations. Often, I choose to have selective social interactions with intent and then return to my studio. It’s not that society is inherently wrong. For me, it is about finding the balance between solitude and the right kind of interactions that fuel my imagination and creativity.

It would seem your work is aimed at stirring the soul and persuades viewers to confront dark subjects like grief, loss, and longing. Why did you opt for such topics? As a photographer, are these the subjects you look for in other’s works as well?

My life, as I knew it, ended at 17 when my sister passed away. There was no choice in that. My new existence was mine to navigate and decipher alone. I think if she were here today, I would have had a very different story to tell. This violent splintering created a definite shift and formed the current path I’m on. Another marker occurred two years ago when the purpose of my work and my transition from photographer to artist presented itself in a town camp outside Alice Springs.

In 2018 at Red Poles, artist Lavene McKenzie and I presented a series of thirteen works addressing our life-changing experiences. That presentation had an existential effect on me, instigating a new wave of motivations to produce more creations that went deeper and explored the past, present and future.

The process of creating new worlds, within natural landscapes, is the only way I know how to translate the experience of this world and to understand my place in it genuinely. Living outside of society also allows me to enjoy the separation from the saturation of external expectations; providing space to challenge and explore the construct of perceived normality honestly.

In other people’s work, I look for intent. Any form of control is good as well; for example, someone who creates work that takes a lot of effort or involves a repetitive process. My process is a form of meditation, expunging poison from the body. It’s like breathing.

Why did you choose to document Australia’s First People’s lives, especially those residing in South Australia, Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) land and surrounding areas?

Growing up we were taught of the valiant pioneers that toiled vigorously to bring prosperity to this savage land or the cheeky antics of Ned Kelly, the infamous Australian Robin Hood, and of the lining up, hand over heart swearing allegiance to the Queen, but never the real history of this land. It’s an aspect that continues to be ignored even today. I wanted to undo the status quo.

Once I started researching and truly listening, the facade of the known historical construct about the Aboriginal people came crashing. Only the truth remained. I have to thank my father for that.

I was working in design in Adelaide when my father called me late one night and said he and his friends were going to ride pushbikes from Coober Pedy to Oodnadatta, a journey of 197 km. They’d planned the ride with a group of youngsters from the Indigenous community and asked if I could take pictures of the trip. At that time, I didn’t even know how to operate a camera, let alone manage the lighting elements. The night before my trip to Coober Pedy, my father rang again asking if I could film the journey too! Armed with my third-hand rickety plastic tripod and a $350 Nikon crop sensor d90, I set out north into the red dirt.

Somewhere along the way, I began to see the world differently, and my attachment to material possessions gradually seemed to disappear, replaced by a deep relationship and connection to something much more significant than myself. Finally, I felt I could quit being busy, self-protecting my conscious mind from the darkness. My mind had quietened, and a strong sense of purpose filled the areas once occupied by manic thoughts.

That’s when the urge to explore these lands and their inhabitants crossed my mind. I loved my journey and knew I had to return with better equipment to spend time there and make an effort to bring to light the vast number of stories about the nation’s First Peoples.

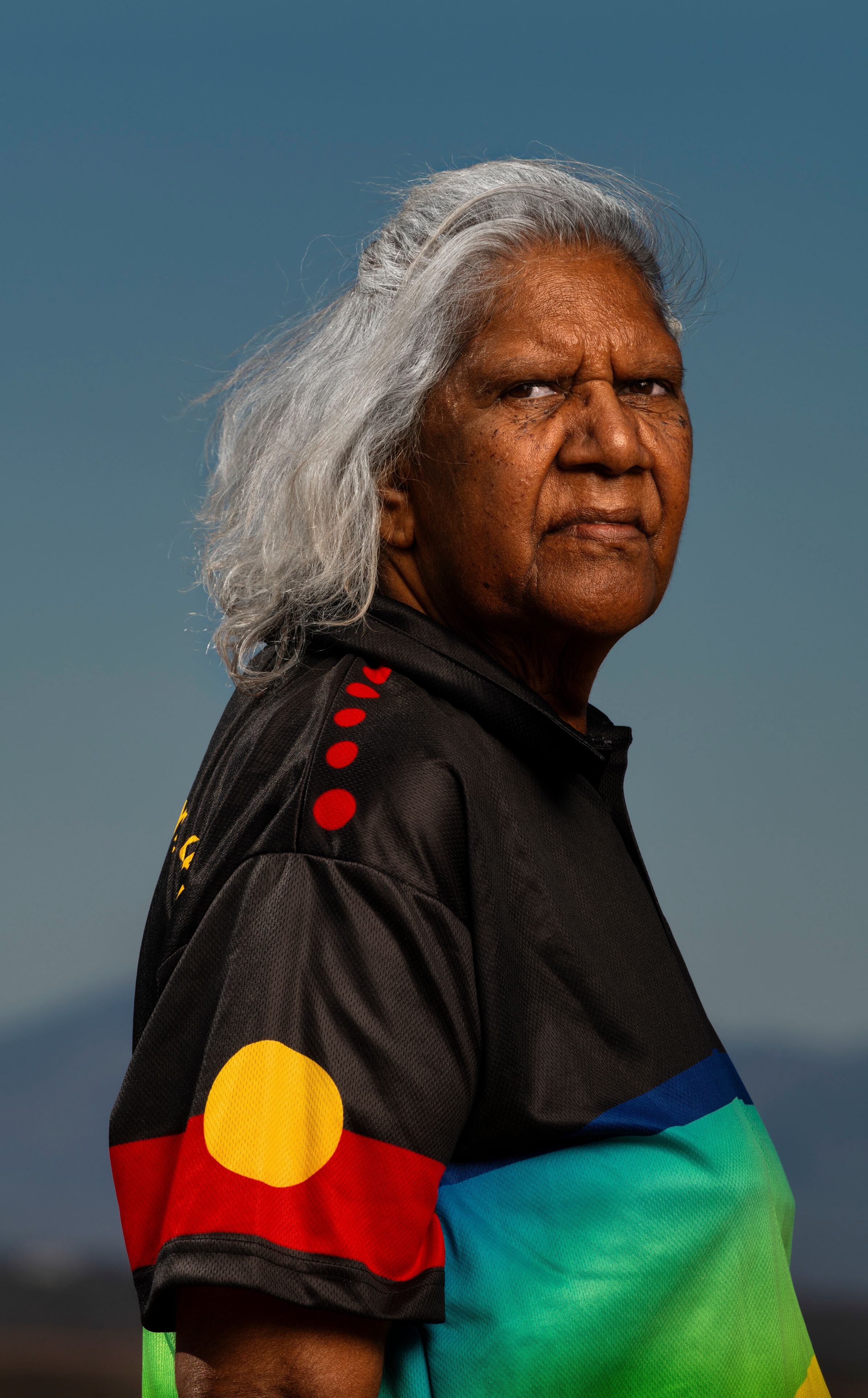

Another incident that strengthened my resolve to feature the stories of Aboriginals occurred last year. I built a series of films and portraits for NAIDOC 2019 theme ‘Because of Her I Can’. The challenge was to gather short, genuine interviews to be edited together into a compelling narrative. In the end, it came down to a simple question – “Who is the person who made you who you are today?” The process of this project changed the way I looked at my work as well as streamlined the benchmark to reveal a simple life, built on truth without the trappings and distractions of imposed expectations.

I’ve applied this methodology to every project since, even commercial work outside of the community.

How do you initiate discussions with Indigenous Australians? Are they hesitant or happy to tell their stories?

Since 2012 I’ve lived within various Indigenous communities, rather than having a fleeting travel relationship with the residents there. This was a conscious choice and one that aligns with my immersive art process and subsequent practice.

I lived in Coober Pedy for five years, working with Elders on mental health, and understanding the oral history at Umoona Aged Care Aboriginal Corporation (UACAC) and Umoona Tjutagku Health Service Aboriginal Co (UTHSAC). I also lived in Amata and Pukatja for a while, followed by a short stint in Mutitjulu.

I also made Davenport Community my home for three years, running an extensive mentoring program there. Living and working amongst Indigenous Australians allowed me to view their way of living and comprehend their passionate reverence to their ancient culture.

I meet a lot of people and rarely ask them to do a certain thing for my pictures. I do tend to talk to them about life in general, and take photos as they speak. This approach helps me get photos that are authentic, devoid of unnatural posing.

Organically, committed sociality allows events to unfold as they happen, not chasing a specific image or scenario and the portraits are rarely staged or contrived.

The stories that come out of these friendships are by-products of a walking alongside mentality; the intent is to shine a light onto untold stories that are often ignored or overlooked by the media and the popular tourist narrative.

In our earlier discussions, you mentioned that through photography, you want to “explore your state of not belonging.” Why is this almost vagabond element an integral part of both your professional and personal life? And, how do you want to achieve this state through your art?

Living outside of society is an incredibly liberating form of existence. However, it isn’t as easy as it appears, and navigating the two systems in this age can be quite complicated. Moving between Aboriginal communities, friends and family, pastorals and greater society while retaining authenticity is extremely difficult and something that needs constant attention combined with aggressive accountability. To challenge the majority, while expunging blind faith, often leads to heated discussions and disagreements, which ultimately results in a life on the fringe and an existence of belonging to nothing and no one.

Subconsciously I created a series (Hidden lands) around this idea; documenting found objects with beautiful light to contrast the horror and macabre installation of human made elements within nature. Through investigation and relentless challenging of drive and process, this reality has become more transparent and yet somehow no less daunting.

The most significant by-product of this type of existence is the ability to find joy in simplicity, without the inundation of constant instant gratification and external stimulation.

You describe your art as “a unique-blend of site-specific installations and distinctive lighting techniques.” How did you arrive at this particular style? Was it a journey of trial and errors?

In all creative endeavours, the learning style engaged has been trial and error. The battles won, along with numerous failures endured have enabled me to lay the foundation on which I built my next move. In 2015 there wasn’t much information available online about advanced off-camera lighting, and many suppliers were in the dark when it came to inter-brand compatibility and functionality. The only way to develop these techniques that made up my process and style was to try and fail, tweak elements, buy and sell equipment and work through the technical maze. Being remote also meant you couldn’t just walk into photography wholesalers and try a new trigger or modifier, so a lot of the products were either returned or sold.

Scouting locations isn’t really a task. Again, it goes back to the resource base. The combination of both my lifestyle and art form gave me the advantage of a large location and application list, whether it be places I’ve made a camp at, an interesting backtrack or a hidden waterhole for a swim. Every element is addictive and compounds together to create the final works which can sometimes take up to a week or more to create. The troop carrier houses a multitude of c-stands, eight 600w studio heads, paints, rigging materials, smoke machines and huge industrial stage fans enabling the creation of large-scale productions over longer duration of time. Some locations are seasonal as well, so I plan visits to different parts of South Australia based on these to harness the landscape’s varying elements dependent on the story being told through the works.

Your photos have caught the attention of the National Portrait Gallery! Please tell us about that experience.

It’s been great to work with the National Portrait Gallery since I started experimenting with dSLRs. I was always looking for robust platforms, and the NPPP is a perfect avenue for community stories to garner a national profile. The subjects are not explicitly chosen or set up; I prefer these to present themselves throughout the year, again removing myself from the works. I’ve met a lot of inspiring people at the openings and continue to stay in touch with them.

Which pieces of art have inspired you and why?

My main inspirations come from films like Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal or by the challenge of creating a work based on a story or feeling. I am drawn to artists who have had deep formative year experiences and clearly defined life markers. Bill Viola is another artist I can relate to who uses his early childhood experience of almost drowning to find a new world of beauty underwater.

Gregory Crewdson works tirelessly, and his attention to detail pays respect to the stories he is telling through these complex, expansive site-specific works.

I am also inspired by sculptor, artist and photographer Andy Goldsworthy who spent most of his early career out in the Scottish marshes surrounded by creeks and rivers. His quote, “It’s just about life and the need to understand that a lot of things in life do not last,” moved me tremendously.

What are your plans for the future?

At the moment I’m based near Flinders Ranges, South Australia finishing off the final works for the Interrupted Collaboration with a Nhanda and Nyoongar man Glenn Iseger. We have been working on it for a year now.

I’ve also begun the pre-production for a three-part Elementals Series. The first stage is Survival which has been an exciting headspace to be in during this pandemic. I often wonder if I will ever master photography and be able to move onto the next discipline. That’s a slightly rhetorical question that can only really be answered by time.

To view Dave’s work, head over to his website.